Resources

Statements

Green Hydrogen and the Tsau ||Khaeb (Sperrgebiet) National Park

On this International Day for Biodiversity, Wednesday 22 May 2024, the Namibian Chamber of Environment (NCE) is pleased to share with you its Position Paper on the proposed Green Hydrogen developments in the Tsau ||Khaeb (Sperrgebiet) National Park (TKNP) in Namibia (see below).

The TKNP is within one of only 36 global biodiversity hotspots. It is Namibia’s most biodiverse national park. It has more endemic and near-endemic species (species that occur no-where else on earth) than any other national park in Namibia. The global importance of this national park is greater than all the national parks in Germany, which would be the main recipient of green hydrogen produced in the TKNP. The damage to the integrity, biodiversity, landscape, sense of place and future tourism will be immense, all in the interests of serving the relatively short-term energy needs of mainly Germany and some other parts of the EU. We don’t believe that the people of Germany would allow the destruction of any of their national parks for energy production, and we ask them to tell their government that it is morally wrong to offshore the environmental costs of their energy needs to Namibia.

The Namibian Chamber of Environment, an IUCN Member, fully supports the IUCN position that initiatives to mitigate climate change should never come at the expense of biodiversity. These are the two greatest environmental challenges facing the planet and it is profoundly wrong and counter-productive to mitigate one at the expense of the other.

With such potential damage to one of Namibia’s most globally important national parks and to our biodiversity, could this hydrogen really be called “green”? We would suggest that RED hydrogen is a more appropriate name – because industrialising the TKNP will drive many species onto the biodiversity Red List and hydrogen produced in the TKNP will carry the blood of its lost biodiversity.

We call on the Namibian government, the German government and the European Union to immediately commission an independent and transparent Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) of the green hydrogen sector in Namibia with broad public consultation, to plan the most effective way forward for Namibia. We also request a meeting with the German Minister of Environment to explain the importance and significance of the TKNP and the damage which the production of green hydrogen in that sensitive area will do to its biodiversity, its future and the reputations of all who facilitate its development.

NCE Position on harvesting of hardwood timber in North Eastern Regions of Namibia and associated deforestation

The Namibian Chamber of Environment (NCE) is deeply concerned about the current commercial harvesting of slow-growing hardwood trees in the north east of Namibia (mainly Kavango East and West, northern Otjozondjupa and Zambezi).

Botswana's engagement with communities over elephant management

Namibian conservation organisations support Botswana’s democratic processes regarding elephant management.

We, as Namibian conservationists, including environmental NGOs, researchers, community representatives and conservancies, hereby join a group of international conservationists in voicing our support for Botswana’s consultative process to address the challenges associated with managing its large elephant population. We applaud President Masisi and Botswana’s parliament for establishing the consultative process that looks to balance wildlife conservation with the needs and aspirations of the citizens of Botswana.

NCE Position on Cabinet decision of 6 December 2017 on a zero pilchard and sardine quota for three years

The Namibian Chamber of Environment (NCE) would like to congratulate the Namibian Cabinet and the Ministry of Fisheries & Marine Resources (MFMR) for making this important decision. We recognise that the Ministry is sometimes placed in a difficult position, and has to weigh up fish resource sustainability with business interests and jobs. However, it is important that the health of the fish resource must take priority. Because without a healthy resource, there will be no long-term businesses and no long-term jobs. Responses to a declining resource base must be taken quickly – and far sooner than was the case with the pilchards - in fact, as soon as a decline is detected, not when fish stocks are so low that a recovery is really precarious. Without a healthy, productive fish resource, both the marine ecosystem and the fishing industry with its associated jobs, will suffer. This principle of managing for a health resource base, applies to all resource components in the marine ecosystem, and to all primary production sectors, in water and on land. The key indicators in the marine sector – the dramatically declining seabirds such as Gannets and Penguins - were simply disregarded and ignored. So was the advice of scientists.

The NCE supports the need for at least a 3-year moratorium on pilchards and sardines. However, the time period is not the issue. The moratorium should continue until the pilchard stock has reached an agreed healthy threshold, i.e. until the stock has recovered to the point where key marine indicators such as seabirds (Gannets and Penguins) are starting to recover, and where a sustainable quota can be given without jeopardising the marine ecosystem. Given the current extremely low levels of the pilchard population in Namibian waters, perhaps at only 1% of their historic numbers, it may take much longer than 3 years for a partial recovery. The length of the moratorium must thus be based on achieving a threshold stock level, not on a number of years.

During the pilchard moratorium, additional stringent measures and penalties must also be put in place to prevent pilchard by-catch. A moratorium will have little impact if pilchards are simply being caught as bycatch. The MFMR should explain their strategy of how they propose to address this bycatch issue.

The MFMR also needs to work closely with Angola to extend this moratorium into Angolan waters. During the moratorium, the two countries should work to develop an agreement on the sustainable management of the shared sardine / pilchard stocks via a joint sardine / pilchard management plan.

And finally, this pilchard fiasco must direct our attention to the current systems in place regarding fisheries management and quota setting. It is clear that the advice of marine scientists was disregarded in favour of the fishing industry. The evidence provided by declining seabirds was ignored. From a governance perspective, it is just wrong that the industry should have such a powerful voice in determining the management of our fisheries resources. This needs to be seriously addressed. The MFMR has a dual role in the marine ecosystem – (i) of setting production quotas and (ii) of ensuring sustainability and a healthy ecosystem. The Ministry has clearly failed in this second role. Their failure to ensure a healthy ecosystem has led directly to a failure in ensuring economically sustainable production in the pilchard industry – the two are inextricably linked.

The root of the problem goes to a lack of transparency and public accountability within the management of the marine ecosystem. Research data on stock assessments are not made public, how quotas are set are not made public, how quotas are allocated are not made public, catches and by-catcher are not made public, the business arrangements within the sector are not made public. Marine fisheries management is shrouded in secrecy – and these are national resources that the MFMR are managing on behalf of the nation. This needs to change, and it needs to change now. Openness, transparency, accountability and partnership are the underlying attributes that contribute to good governance, good decision-making and sustainability. These attributes seem to pose a threat to the MFMR. This is profoundly troubling. We do not need more fiascos in the marine ecosystem. We need to get the higher-level management systems right, starting now.

Namibian civil society deplores the US President’s decision to abandon the Paris Climate Agreement

US President Donald Trump announced on Thursday 1 June 2017 that the United States, one of the world’s largest emitters of greenhouse gases that cause climate change, will withdraw from the Paris Climate Agreement.

The USA joins only two countries in the world that have not signed the Paris Agreement. The other two are Syria, which is in the midst of a civil war, and Nicaragua, which felt the goals were not ambitious enough. In the view of the Namibian Chamber of Environment, this decision is short-sighted. It will have negative consequences for the US economy and for the international community, to which Namibia will not be immune.

What is the Paris Agreement?

The Paris Agreement, adopted by 196 countries at the global climate negotiations (or more formally, the Conference of Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change) in Paris in December 2015, is the result of years of difficult and contentious negotiations among global leaders. It sets a path towards addressing climate change, a major global challenge which threatens to undermine progress towards sustainable development and exacerbate instability, disproportionately affecting the world’s poorest people and countries. It also represents an unprecedented achievement in international diplomacy: it is the first international climate change agreement that includes voluntary commitments for all countries to take actions to address climate change. These commitments, known as “nationally determined contributions”, are to be reviewed every five years to allow for a gradual increase in the level of ambition.

The Paris Agreement entered into force in November 2016, after 55 countries representing at least 55% of global emissions agreed to join. The United States, under the Obama administration, played a key role in the international negotiations that led to the historic agreement. In October 2016, the US and China – the world’s two largest emitters who together account for 38% of global greenhouse gas emissions - jointly signed on to the Agreement.

Why did the US pull out?

Trump's decision to pull the US out of the Paris Agreement, in line with his campaign promise, is based on the argument that the Agreement ‘disadvantages the United States, to the exclusive benefit of other countries, leaving American workers and taxpayers to absorb the cost in terms of lost jobs, lower wages, closed factories and vastly diminished economic production'. The decision has received widespread criticism, both domestically and internationally. Furthermore, the claims Trump made to support the decision have been called into question.

What are the implications for the US?

The claim that US commitments to address climate change will cost the US as much as 2.7 million lost jobs by 2025, is based on a highly disputed study by the conservative consulting firm National Economic Research Associates. In fact, growth in renewable energy investments would provide many more jobs than fossil fuels, and improve economic output. Already, solar power alone employs twice as many workers in the USA than coal, natural gas, oil and the petroleum industries combined. Adding in wind and nuclear, clean energy outpaces fossil fuel jobs almost three-fold.

Staying in the Paris Agreement makes business sense for the US. Actions to put the US economy onto a lower carbon growth path would strengthen competitiveness, stimulate job creation and growth in clean technologies and markets, and reduce business risks such as the impacts of declining water supply and agricultural production on supply chains. Business leaders, including some of the world’s major energy companies, view the Paris Agreement as an important signal that will facilitate new opportunities in clean energy and other sectors, and over 1,000 businesses in the US have urged Trump to stay in the Agreement. City and State governments across the US have expressed their support for the Paris Agreement, and several states including California and Hawaii are pushing through measures to advance its objectives despite Trump’s announcement. The majority of American citizens are in favour of the US remaining in the Paris Agreement.

The US withdrawal from the Paris Agreement will also have implications for the country’s role in international diplomacy, both in the climate negotiations, in which the US will lose its bargaining position, and in other international issues such as trade and security, in which the US stands to lose its credibility as a responsible global power.

What are the implications for the world?

The Paris Agreement is significant because it requires all nations to curb their emissions, including major developing country emitters China and India. In this regard, it differs from its predecessor - the Kyoto Protocol – which only set emissions reduction targets for developed countries, and which the US did not ratify for this reason. Its inclusiveness - the foundation of the Agreement’s legitimacy – is thus undermined by the US withdrawal. Nonetheless, although it is undeniably a setback, there is little evidence to suggest that the US withdrawal will have any major impact on the global momentum towards addressing climate change.

Both China and India have reiterated their commitment to the Paris deal in recent weeks and are investing heavily in renewable energy. China has been reducing its coal consumption for the last three years and plans to build more than 100 new coal-fired power plants have been scrapped. India has also slowed the construction of new coal-fired plants and will likely meet its goal of generating 40% of its electricity from non-fossil fuels by 2022, eight years ahead of schedule. That they are investing in renewables with tens of millions of their people still without electricity and other basic services, shows that renewables are now widely accepted as an economically competitive and financially viable investment option. Diplomatically, China is well positioned to step up to fill the leadership void that the US has left as a major power in the climate negotiations and a leader in green energy technology.

Furthermore, global momentum on tackling climate change is increasing fast. Businesses and investors are increasingly recognising the threat that climate change poses to stability and security to their investments, as well as the enormous opportunities it presents for innovation and expansion. Last month, a coalition of over 280 institutional investors that collectively oversee more than USD17 trillion in assets sent a letter to the G7 countries urging them to uphold their commitments to tackle climate change.

Perhaps the most critical impact of the US pulling out of the Paris Agreement is that Trump also pulled out of the US pledge of USD 3 billion toward the Green Climate Fund. This fund was set up to support developing countries to transition towards low carbon, climate resilient development pathways, and has already received over USD10 billion in pledges. The US has already transferred USD 1 billion of its pledge.

Why does it matter to Namibia?

As an arid country with a high dependence on climate sensitive sectors such as agriculture, fisheries and tourism, and over three quarters of the population reliant on subsistence agriculture for their livelihoods, Namibia is highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. Climate change exacerbates existing development challenges including inequality, poverty and land degradation, and threatens to undermine progress towards sustainable development, a goal which is firmly entrenched in the Namibian constitution, and in our Vision 2030.

Although its contribution to global greenhouse gas emissions is negligible, Namibia punches above its weight in the international climate change arena. Namibia was one of the first countries to access resources through the Green Climate Fund, with the accreditation of the Environmental Investment Fund (EIF) to access funds in 2015 and the first two projects – which advance climate resilient agriculture in north-eastern Namibia and empower rural communities through climate resilient community based natural resource management – last year. Namibia’s “nationally determined contribution” sets out ambitious targets to ensure a low carbon development path and to strengthen resilience of communities and ecosystems to climate change through actions across all the key climate sensitive sectors of the economy. However, many of these commitments are contingent on financial support, with the Green Climate Fund identified as a key source of funding for achieving its climate objectives. In this regard, Namibia is not immune to the impacts of the US withdrawal from the Paris Agreement.

Namibia has a long history of constructive partnership with the US to advance sustainable development issues, including through USAID support to CBNRM programmes, the Millennium Challenge Account and more recently the Power Africa initiative which is supporting efforts to advance clean energy investment. The US decision to withdraw from its commitments on climate change is a disappointing signal of what the future of US bilateral engagements on climate issues may hold. Nonetheless, Namibia is committed to addressing climate change, and will continue to build on the strong momentum that exists both nationally and internationally to achieve the objectives it has set.

NCE’s response

On behalf of Namibian civil society, the Namibian Chamber of Environment deplores the decision of President Trump to withdraw the US from the Paris Agreement. This decision will undermine the US legitimacy as a partner in advancing sustainable development in Namibia. It undoes the work of years of delicate US diplomacy and leadership that united 196 countries with vastly different interests and circumstances around a common goal to address a critical global challenge. It will impede the achievement of the objectives of the Green Climate Fund, an important funding mechanism for climate compatible development for Namibia and other developing countries. Nonetheless, Namibian stakeholders remain firmly committed to addressing climate change. Namibian civil society and private sector will continue to work closely with government and development partners to strengthen the resilience of communities and ecosystems and to ensure a safer, low-carbon future. The NCE stands ready to work with all partners in the pursuit of this goal.

The Namibian sardine fishery – taking a “gamble” on a sustainable future

Various newspaper articles in the last two weeks quoted the Minister of Fisheries and Marine Resources, Bernard Esau, as admitting that he ignored the scientific evidence and resulting recommendations for a moratorium on sardine (pilchard) fishing from his own fisheries scientists. Instead, he “took a gamble” in allocating a fishing quota for sardines for 2017. This is most disturbing at many levels.

Namibia has been praised internationally for its forward-thinking Constitution which, in Article 95, safeguards the “maintenance of ecosystems, essential ecological processes and biological diversity of Namibia and utilization of living natural resources on a sustainable basis for the benefit of all Namibians, both present and future […]”. Moreover, the Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources (MFMR) has been recognized internationally as a proponent of the Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries (EAF) Management, for its commitment to responsible fisheries management (with the former Minister Abraham Iyambo being a co-chair of the committee drafting the Reykjavik Declaration on Responsible Fisheries in the Marine Ecosystem in 2001), and for being a signatory to Agenda 21 and adopting the Plan of Implementation that was drafted at the World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD) in 2002. Among many other relevant commitments related to improving food security, efforts to reduce the rate of loss of biodiversity, the implementation of an ecosystem approach to fisheries etc., this plan calls specifically for the adoption of urgent measures to rebuild depleted fisheries stock to maximum sustainable yield levels by 2015.

The Namibian sardine stock was first targeted by the purse-seine industrial fishery after World War II. The industry grew rapidly during the 1960s, with a peak in 1968, when declared catches were 1.4 million tonnes. Actual catches were probably much higher as much of the sardine caught was used for fishmeal and the stock was also fished in southern Angola. This level of exploitation was grossly unsustainable and as a result the stock crashed between 1970 and 1972. Following this decline, the fishery targeted anchovy and juvenile horse mackerel, which in turn led to a crash of the anchovy stocks but did not result in a recovery of the sardine. Most canneries closed down in the late 1970s and early 1980s, with the loss of several thousand jobs and a drastic drop in production of an abundant, healthy and affordable food. Already in 1982 fisheries scientists called for a moratorium on sardine fishing in order to let the stock recover to sustainable levels but were ignored. In the 1950s and 1960s sardine stocks were first estimated, varying between 5 and 11 million tonnes. Since then, it appears that the biomass of sardine in our waters has declined currently by 99% or more.

In recent decades, scientists worldwide have demonstrated the key role that “low trophic level” forage fish species (i.e. those that feed on plankton and in turn provide food for marine predators) - such as sardines and anchovy - play in the marine ecosystems, and how a drop in biomass of such species to low levels severely affects the marine food chain, various fisheries and top predators. Many of these studies have highlighted the degradation of the Namibian marine ecosystem as a “worst case scenario in the 21st century”, where a depleted sardine stock has led to drastic changes in the essential ecological processes of the Benguela ecosystem that also affects other fisheries resources such as valuable predatory fish like hakes and perhaps tunas. Some of Namibia’s seabirds, once reliant on sardines, have been forced to switch to less suitable, poor-energy prey. This has been the primary reason for the declines of endemic seabirds such as African Penguins, Cape Gannets and Cape Cormorants, all of which are now at serious risk of local extinction.

Several regional studies made under the auspices of the Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem programme (BCLME) found that the low biomass of sardine, the continuation of fishing and lack of serious measures to promote the recovery of this stock in Namibia had serious detrimental consequences on the ecosystem, its biodiversity, levels of unemployment, the economy of the coastal towns, as well as food security in the region. Those studies called for a more rational and scientifically based management of this fish stock to allow its recovery, as well as more transparency in the determination and allocation of fishing quotas.

A sardine stock rebuilt at maximum sustainable yield level (as mandated by the Namibian Constitution, the WSSD Plan of Implementation and the fisheries policies in place since Namibian independence) would mean a potential annual catch of close to a quarter million tonnes or more in most years. This would make the sardine sector the primary fisheries sector in terms of food production, and second behind the hake industry in export value. This in turn would mean several thousand additional jobs, as opposed to the few hundred temporary seasonal workers at present which, in part, have been sustained recently through the import of frozen sardines from Morocco for the canneries. The marine ecosystem processes would be greatly improved and other sectors of the Namibian fishery would probably benefit from a more productive and healthier ecosystem. The main cause of the decline of our endangered seabirds would be resolved - a great step towards halting the loss of biodiversity.

Given the current state of the sardine sector, a moratorium of several years could be achieved at minimal costs. Current jobs could be maintained with the sourcing of fish from elsewhere as is being done already, or by redeploying employees temporarily in other sectors. However, repeated calls by scientists for a moratorium on sardine fishing to allow stocks to recover have been ignored, apart from a single year (2002) when no quota for sardine was granted. However, this measure was defeated that year by sardines being caught as bycatch of other fisheries, as well as vessels registered in Walvis Bay seeking fishing licences in southern Angola.

Bearing in mind the key role that sardines play in our marine ecosystem, the collapsed state of the stock, and Namibia’s commitment to sustainable resource use, the recent announcement of a 14,000 tonne quota for 2017 by Minister Esau raises serious questions on the soundness of the decision-making process that is being followed. While the “Minister may, from time to time …. set a total allowable catch to limit the quantity which may be harvested …” he shall do so “on the basis of the best scientific evidence available ...” (Marine Resources Act 27 of 2000). Given the pivotal nature of sardines in the Benguela ecosystem, a seriously precautionary approach should be taken, erring on the conservative side. Minister Esau seems to dismiss scientific recommendations, including that of his own scientists, as a “misconception”, despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary. Instead, he suggests that sardines simply may have moved to deeper waters, a statement that appears to be a personal view that is seemingly not backed by any solid data. Minister Esau is gambling with the ecological stability, biodiversity, productivity and economy of Namibia’s marine ecosystem. Is it sound governance to allow such decisions, on the long-term future of Namibia’s marine ecosystem, to be taken by one person on a gamble?

Minister Esau further states that the decision was done in consultation with the Marine Resources Advisory Council (MRAC), which currently comprises 13 members, of which at least five members represent the fishing industry or have fishing interests. Only one practising fisheries scientist serves on the council (and notably none from MFMR), essentially biasing decisions in favour of the fishing industry. It is unclear what advice the MRAC gave to the Minister, as so many aspects of marine fisheries lack transparency. Transparency is urgently needed on estimated fish stocks, on decision-making processes, on the minutes of the discussions held with the MRAC, as well as the scientific and socio-economic recommendation report.

And most important, urgent measures are needed to promote the recovery of the stock. These should include:

- a moratorium on sardine fishing (including fines on sardine caught as bycatch) until the stock has recovered to sustainable levels – for at least three years - as per the Namibian Constitution, national policies and international commitments;

- rigorous scientific research on stock size and related ecosystem aspects to be continued and intensified;

- implementation of agreed EAF management principles, including long term sustainability of ecological (including biodiversity), economical and social wellbeing;

- development of Marine Protected Areas, specifically to protect key spawning and nursery areas;

- an agreement with Angola on the sustainable management of shared sardine stocks, ideally via a joint sardine/pilchard management plan.

Namibia’s sardines belong to all Namibians. As the official custodian, MFMR is tasked with their sustainable management. Instead of being merely “a gamble”, this task needs to be carried out in a transparent, equitable manner that is based on science-based decisions that heed national and international obligations.

NCE meets with Ambassador Qiu Xuejun of the People’s Republic of China to Namibia

After receiving an Open Letter about wildlife crimes committed by some Chinese nationals in Namibia, the Chinese Ambassador of the People’s Republic of China to Namibia, His Excellency Qiu Xuejun, invited a delegation of representatives from the Namibian Chamber of Environment (NCE) to meet with him and his delegation at the Chinese Embassy in Windhoek on 4th January 2017 to discuss the matter.

An open and frank exchange of views took place, followed by a constructive discussion of how to move forward. The Ambassador and his delegation stated that the Chinese government is absolutely opposed to all forms of criminal activity by Chinese nationals in Namibia, including wildlife and environmental crimes. The Ambassador also expressed a desire that his embassy, the Namibian environmental NGO sector and the Namibian government work together to effectively address the problem.

Offshore mining of marine phosphate

- Clearance to proceed is valid for a period of three (3) years.

- If impacts are found to be greater than expected, and no feasible and acceptable mitigation measures are implemented, then the operation shall be closed and the Environmental Clearance Certificate withdrawn.

- Bi-annual (twice per year) reports on the implementation of the Management Plan (and the monitoring required therein) must be presented to both the Ministry of Environment and Tourism (MET) and to the Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources (MFMR).

- Dredged seabed and water column monitoring must be conducted on a regular basis with reports submitted to MET quarterly.

- The proponent must fund the establishment of a centre of excellence to monitoring the impact of phosphate mining and to produce generic standards and guidelines for the sector in future.

- Data from the monitoring must be freely shared with the competent authorities.

- The best available technology must be used to have least environmental impact.

- The mining and processing techniques will be reviewed annually against monitoring data, to be done jointly by the proponent and the regulator.

- Separate environmental clearance must be obtained for the onshore processing plant.

The capture of rare and endangered marine animals for the aquarium trade

The Namibian Chamber of Environment firmly support s the environmental clauses in the Namibian Constitution, including the sustainable use of natural resources for the benefit of all Namibians, both present and future. However, the Chamber is opposed to the capture of rare and endangered marine animals for the Asian (and any other) aquarium trade for the following reasons:

- Conservation: a number of the species in question are uncommon, rare, seriously declining in numbers or comprising small isolated populations in Namibian waters. Every effort should be taken to protect and conserve these animals (e.g. whales, dolphins, penguins), and there should be a totally closed - door policy to any exploitation of these species other than through carefully managed tourism. Many of these species are endangered, both locally and internationally and are on the IUCN Red Data list.

- Sustainable use: removing animals from small, isolated, endangered and/or declining populations, particularly breeding individuals, does not constitute sustainable use. Such removal will disrupt social structures, result in reduced breeding and may impact on group hunting efficiency. The principle of sustainable use, which works so well in the wildlife sector in Namibia, is linked to land owners and custodians having long - term rights as well as long - term incentives and responsibilities within a regulated system. External pillaging of renewable resources carries no responsibility for the long - term health of those populations. The Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources, as the responsible custod ian on behalf of the Namibian nation, must ensure that this sort of senseless removal of valuable resources does not occur and is never again considered.

- Misrepresentation: we understand that the proponent has argued that these species occur in “excess numbers” and that they are a cause of dwindling fish stocks. People familiar with Namibia’s coastal and marine ecosystem are perfectly aware that whales, dolphins and penguins are uncommon, rare, declining, threatened, and have an insignificant impact on fish stocks in Namibian waters in terms of competition with the fishing sector. Indeed, the opposite situation applies, with these marine species suffering from the decline caused by over - fishing, particularly before Namibia obtained control of its marine zone after independence, and particularly resulting from the collapse of the sardine and pilchard fisheries. The proponent is simply using populist misrepresentation and untruths to support an indefensible proposal. Indeed, the Namibian Chamber of Environment would like to see a total closure of the pilchard fisheries for enough years for this resource to recover to levels where it would once again be a viable industry, and a viable food resource for marine birds and mammals.

- Ethics: wild, wide - ranging species are generally unsuited for captivity. Animals suffer high levels of stress and high rates of mortality in captivity. It is widely considered to be unethical and morally questionable to remove such species from the wild and place them in captivity.

- Reputational damage: Namibia has an excellent international reputation in the fields of conservation, sustainable natural resource management and sustainable development. This reputation would be seriously tarnished if approval for the capture of these species were to be given by the Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources.

- Local beneficiation: no long - term benefits would accrue to Namibia and the Namibian people from allowing such a capture of endangered and CITES - listed marine wildlife in Namibia. These species play a far more important role within Namibia’s marine ecosystem and within the Namibian economy. Indeed, the reputational damage that this would do to Namibia would have a negative impact on Namibia’s tourism industry. Tourism is one of the main pillars of our country’s economy and, in the current difficult climatic and economic circumstances, the fastest growing sector of the economy. We should not be doing anything that would negatively impact its future growth.

In conclusion, our view on the application to the Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources revolves around the issues of wise and ethical use of renewable resources, benefits from natural resources to Namibia and her people, conservation of rare and threatened species, and potential reputational and economic damage to Namibia. This application does not promote or contribute to sustainable use of natural resources but rather undermines these principles. The idea behind the application resembles more an uninformed attempt to pillage valuable resources from Namibia’s waters with absolutely no concern for the implications and consequences. The animals in question are far better left in their natural habitat and protected for the important ecological roles they play in our coastal and marine ecosystems and for their tourism value. We are confident that, after due consideration, the Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources will arrive at the same conclusion.

Drought Relief Bulletin – September to October 2019

Drought Relief Bulletin – July to August 2019

NCE newsletter 1: November 2016

Drought Relief Bulletin – September to October 2019

Drought Relief Bulletin – July to August 2019

NCE newsletter 1: November 2016

Symposiums & Meetings

Mining and Environment Workshop, June 2017

In June 2017, a workshop was held for the Environmental Departments of all mines in Namibia to develop a 3-year environmental strategy and action plan for the mining sector. We see this extending to the development of a "Good Practice Guide for mining in Namibia" and a set of environmental criteria for inclusion of the mining sector into the Eco Awards Namibia programme.

This falls under the NCE programme area "National Facilitiation".

Presentations from the symposium can be downloaded from the Environmental Information Service (EIS).

Symposium on animal movements and satellite tracking in Namibia

Presentations and outputs from the Symposium on animal movements and satellite tracking in Namibia held on the 23rd to 25th of November 2016 at Otjikoto Game Park and Education Centre.

All presentations and other outputs can be downloaded from The EIS by clicking on the link below.

This falls under the NCE programme area "National Facilitiation".

Mining and Environment Workshop, June 2017

In June 2017, a workshop was held for the Environmental Departments of all mines in Namibia to develop a 3-year environmental strategy and action plan for the mining sector. We see this extending to the development of a "Good Practice Guide for mining in Namibia" and a set of environmental criteria for inclusion of the mining sector into the Eco Awards Namibia programme.

This falls under the NCE programme area "National Facilitiation".

Presentations from the symposium can be downloaded from the Environmental Information Service (EIS).

Symposium on animal movements and satellite tracking in Namibia

Presentations and outputs from the Symposium on animal movements and satellite tracking in Namibia held on the 23rd to 25th of November 2016 at Otjikoto Game Park and Education Centre.

All presentations and other outputs can be downloaded from The EIS by clicking on the link below.

This falls under the NCE programme area "National Facilitiation".

Hot Topics

Our ‘Hot topics’ section has a new home. Since 2021, most news, views and true stories from Namibia can now be found on our partner website: Conservation Namibia.

‘Hot topics’ is a section for opinion pieces, blog-type articles, and thoughts on topical conservation issues. The articles reflect the opinions of the individual writers and may not necessarily concur with the views of all NCE members.

Bush Talks: Conversations to Foster Sustainable Biomass Utilization

Statement on Potential Namibian Biomass Export to Hamburg

Are you eating plastics for dinner?

Conservation Partnerships to combat wildlife crime in Namibia

Feral horses in the southern Namib parks

Response to Concerns About Wildlife Numbers in Namibian Communal Conservancies

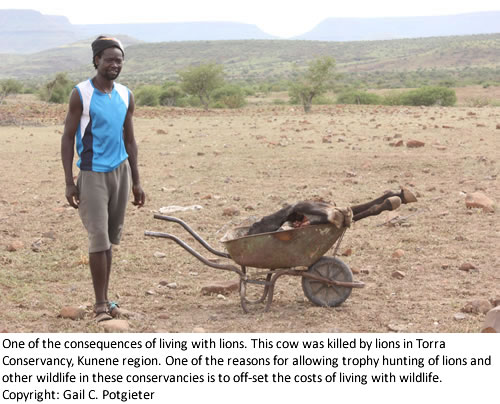

We posted an article entitled “The Future of Hunting” because we believe that the author is absolutely correct in stressing the three key principles that should be followed by the hunting fraternity, and which should be enforced, namely (i) transparent implementation of and compliance with scientifically grounded sustainability rules, (ii) full recognition of the role of local rural people in wildlife management and their rights and responsibilities regarding natural resource management, and (iii) the behaviour of hunters in the field and how they conduct themselves and present themselves to the public.

We clearly need to correct the conspiracy theories being peddled regarding the institutional arrangements concerning the organisations that support communal conservancies in Namibia. First, WWF in Namibia is a programme office of WWF-USA. It is not a country office. No environmental NGO in Namibia works under WWF. Namibian NGOs supporting conservancies are all independent organisations with their own, independent boards. Second, NCE is an independent, umbrella membership-based organisation for mainly Namibian environmental NGOs. WWF is not a member of NCE and has no position or involvement in any NCE governance structure or decision-making.

We need to explain the arrangements between the Namibian NGOs that support communal conservancies. These NGOs have created an umbrella CBNRM support organisation called NACSO (Namibian Association of CBNRM Support Organisations). Only Namibian organisations supporting communal conservancies are eligible for full membership of NACSO. NCE is not a member of NACSO because it does not work at the conservancy level. Non-Namibian organisations working on CBNRM, such as WWF, although a highly valued partner, do not qualify for full membership – they are Associate Members with no voting rights. This has been the situation for almost two decades.

The decisions made by NACSO are made by their Namibian NGO members which have Namibian boards of trustees / directors. They work to help facilitate and develop conservancies and support their natural resources management and development. NACSO has three working groups through which much of the coordination, information sharing, and support is channelled by the member support NGOs. These are (i) the Natural Resources Working Group, which assists with wildlife monitoring and wildlife management, (ii) the Institutional and Governance Working Group, which supports issues around the management of conservancy committees, AGMs, financial management, etc, and (iii) the Business, Enterprise and Livelihoods Working Group, which helps conservancies set up joint venture initiatives with the private sector (e.g. to establish lodges), as well their own managed businesses (e.g. camp sites, craft centres, local guiding). All these processes contribute to an evolving self-sufficiency, democratisation and sustainable resource-based economy in communal areas, based on people’s rights and responsibilities over natural resources.

Is everything perfect? Certainly not, there are many challenges – but it is vastly better than the situation at the time of Namibia’s independence when rural communities had no rights, were totally disempowered, wildlife numbers were very low and people got no benefits from their natural resources. There is certainly plenty of scope for improvement, and all partners are working with conservancies on a daily basis to continuously help get things better and better. It is a process which is generally moving in the right direction. And like democracy, imperfect as it is, there is currently no better model around.

We also need to explain that the support organisations are only one part of the process in establishing wildlife numbers, trends and quotas. The conservancy members themselves, their community game guards and committees are fully involved (they live with the wildlife on a daily basis), as is the Ministry of Environment & Tourism, and in some areas, also the private sector joint venture partners, e.g. in the tourism sector. Wildlife numbers and trends are determined using a number of methods – fixed route vehicle or foot transects using internationally accepted methods such as “Distance” (used in many parts of the world), observations from game guards, water hole counts, camera traps and periodic aerial surveys. Both the fixed route and aerial survey methodologies applied in Namibia have been reviewed by accredited international scientists and found to be of high standard. Different methods are used in different regions and for different species. There is no one system that gives perfect results for all wildlife in all areas. The most useful approach is to use a combination of standardised methods, and particularly to look at species population trends.

Finally, it is important to understand that wildlife populations are not, and should not be, static. They are increasing and decreasing each year and over longer cycles, while some species (e.g. elephant and buffalo) seasonally move across international borders, further contributing to annual fluctuations in census findings. Without this dynamic nature there is little resilience in ecosystems. And in arid zones, this dynamic aspect is particularly apparent and important. So, animals move over large areas and outside places where they might have been seen last year or the year before. And animals die because of drought. But they recover relatively quickly when conditions improve. This is the nature of arid and hyper-arid zones. The larger the open system, the more robust and resilient it is.

Management of wildlife in arid areas also requires a deeper level of ecological understanding and some aspects might seem counter-intuitive. For example, when entering a dry cycle, it might be appropriate to harvest animals while they are still in reasonable condition, put the income in the bank, so that fewer animals die in the drought, so that those which come through the drought are in reasonable condition and are well placed to breed successfully to start rebuilding the population. This is also better for veld management. The old agricultural subsidy system in Namibia, where the state providing fodder, resulted in too many animals staying on the land and, after the first rains, hammering the veld and not giving it time to sufficiently recover. This was one of the contributing factors that led to the bush encroachment we see today.

Short-term (over a number of years) population fluctuations should therefore not be cause for concern, provided that long-term monitoring and adaptive management mechanisms are in place, that governance systems are working fairly effectively and that the broader public understands that arid systems are very dynamic and that wildlife populations vary in response.

Trading Rhino Horn

An Interview with Dr. Chris Brown by Gail Potgieter.

Recently, the Chinese government attempted to partly lift the ban on rhino horn use in Traditional Chinese Medicine (see this New York Times article). The ban on endangered wildlife in Chinese medicines has never been enforced with any commitment or conviction by the Chinese authorities. The fact that these products, like pangolin scales and many others, have no proven medicinal properties does not seem to deter the growing number of users who presumably get some placebo effect enhanced by the conferred status of being able to afford elitist medication.

Chinese traditional medicine is said to be a US$ 100 billion industry. The Chinese government has identified this as a growth industry, to compete worldwide with Western scientific approaches to medicine – particularly in Africa. If this is the case, we can expect the demand for such Chinese traditional medicines to grow, and pressures on wildlife to similarly grow.

Within this context, Namibia and other African countries must carefully consider their response to the Chinese stance. Some critical questions must be asked before it is too late for our rhino population. Dr. Chris Brown, CEO of the Namibian Chamber of the Environment, believes that legalising the trade in rhino horn could provide a way forward for Namibia and its neighbours to resolve the current poaching crisis and create real incentives for rhino conservation in future. However, such a proposal often provokes serious questions about if it could work, and what the future of rhinos would be under the legal trade scenario. In this interview, I put some of the critical questions to Dr. Brown about legalising the trade and how, in his view, it would contribute to rhino conservation.

Question: Why do you think that legalising the trade in rhino horn is a better option than continuing to improve rhino security in Africa and clamp down on the trade in Asia?

Answer: At the moment, demand for rhino horn is increasing, leading to higher prices, more professional and ruthless poaching gangs, and greater danger to our anti-poaching rangers. I do not believe that we will reverse this trend by simply gearing up and doing more of the same. For those who think this continuing arms race over illegal rhino horn will provide a solution after so many years of not succeeding, I refer them to a quote attributed to Albert Einstein: “Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results”.

Question: How would Namibia supply enough horn for sustainable legal trade, and how do you envisage a transparent monitoring and auditing system would work?

Answer: A national dehorning of all rhinos would take place in national parks (with the exception of those in the immediate vicinity of tourism facilities such as Okaukuejo, Halali and Namutoni in Etosha National Park), and on communal and freehold land, on a two to three year cycle. Each removed horn, as well as all stock-piled horns, would be micro-chipped, a DNA sample taken and a passport issued. Horns would be strategically released for sale to pre-approved buyers under a de Beers type marketing system. The passport would accompany the horn throughout its life. A small royalty would be taken on each sale to cover the cost of dehorning (done by nationally approved teams), DNA analysis, storage, management and sales. The bulk of the horn value would revert to the owner or custodian of the rhinos from whence the horn came, i.e. to the national parks, communal conservancies, private owners, or MET for custodian rhinos.

Question: At the moment, trade in rhino horn is banned by the Convention for International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). How would Namibia start trading rhino horn with this ban in place?

Answer: Ideally Namibia’s trade would be under CITES approval with international monitoring and audit procedures in place. Alternatively, if blocked by the CITES member states, it should trade despite CITES, and then transparent monitoring and auditing becomes even more imperative.

Question: At the moment, all black rhinos in Namibia belong to the state, whilst white rhinos can belong to private owners. How would those living with and/or owning rhinos (including private land owners and people in communal conservancies) see the benefit of the rhino horn trade?

Answer: Current approaches to black rhino ownership should be relaxed to allow private and communal ownership, as is the situation with white rhino. Freeing up legal wildlife markets inevitably delivers conservation dividends. Furthermore, custodians and owners of land should be encouraged to expand their wildlife operations to include both species of rhinos (where habitat is suitable), and land under livestock should be encouraged to expand to include wildlife with rhinos. In reality, no real encouragement would be needed, as market forces would provide all the necessary incentives. To facilitate the process, financial support should be offered, e.g. AgriBank could expand its loan facility to allow farmers to invest in rhinos and other wildlife under approved business and management plans that include adequate levels of wildlife expertise.

Question: If rhino horn sales were legalised, would the rhino owners/custodians be the only beneficiaries, or do you forsee a broader economic impact for Namibia?

Answer: Land under wildlife with rhinos and with an international trade in rhino horn in place would generate far greater returns per hectare than any other form of land use, short of finding a diamond-rich Kimberlite pipe on your land (the diamond resource would be depleted over time, but the rhino horn resource would grow). I have estimated that an international trade in rhino horn would contribute close to N$2 billion per year to the Namibian economy, and this would grow as rhino populations expanded. Tax revenue to the state would be significant. A legal trade in rhino horn would help enable land reform, create jobs, address rural poverty, help adapt to and mitigate climate change, and mitigate many other challenges. In short, there is no other natural renewable resource that comes close to the value of rhino horn that would prosper in the semi-arid and dry sub-humid regions of Namibia and Africa.

Question: This all sounds very good from an economic point of view, but will it have a substantial benefit in terms of rhino conservation – particularly with regards to reducing poaching and illegal trade?

Answer: Dehorning of the national rhino herd would significantly reduce the incentive to poach – the risk-to-reward ratio would be heavily skewed towards high risk and low reward, and the markets would simultaneously be well supplied with legal horn. Some people have said that there may be an increase in rhino calf mortality in areas with lions and spotted hyaenas if rhino mothers don’t have horns. The data is equivocal. Based on limited sample sizes it is not statistically confirmed that calf losses are higher to mothers that have been dehorned. And even if the losses were somewhat higher, this would be largely insignificant against poaching losses of adult animals.

Legalising the rhino horn trade would bring many buyers into the open, where their businesses would be legitimised. Businesses far prefer to be legal, where business terms are well understood, and rules are clear. They would be unlikely to jeopardise their legal standing by dealing in “blood rhino horn”. And DNA sampling would quickly reveal illegal horn on the market. Legal dealers would be inclined to give information to law enforcement on illegal dealers to reduce competition.

Question: The idea of legalising the trade in animal parts inevitably brings up the question of trading in other endangered species – like tigers and lions for their bones, and elephants for their tusks. How do you feel about trading those animal parts?

Answer: The situation varies from species to species. Trade and market forces under specific circumstances can contribute significantly to the conservation status of many species and to achieving desired conservation outcomes. Trade and markets do not work for all and they do not work under all circumstances. Only in cases where markets can promote the conservation status of wildlife, are they worth pursuing. Species that are typically unsuited to market forces are slow-breeding, occur at low density and are difficult to monitor and manage. Examples would include pangolins, large birds of prey and some marine mammals. Circumstances that would be unsuitable for market forces to deliver good conservation outcomes are where rights, responsibility and accountability over wildlife have not been devolved to the appropriate level of management by means of policy and legislation, where institutional arrangements to administer and manage the resources are not adequate, and where there is a weak regulatory framework. It is important to note that these operational conditions do not need to be perfect – they need to be sufficient to deliver conservation benefits and have a positive trajectory over time.

We need to clearly differentiate between the tiger and lion bone industry and that of rhino horn. Rhino horn is a renewable resource. It can be harvested without harm to the rhino - the horn simply regrows. While this is happening, rhinos fulfil their ecological role in the environment, breed and, through their huge value, safeguard landscapes under natural vegetation and provide collateral protection to other indigenous biodiversity. And if this initiative is strategically linked to incentives for open landscapes, it could turn around the harmful game fencing mania we currently face, where the landscape is fragmented and wildlife populations become increasingly isolated. Indeed, the value of rhinos and their horn could be the economic driver for rewilding much of Africa. Africa could then really build on its global comparative advantage – its wildlife – as a core plank for long-term development.

By contrast, there is no conservation value to be had from the tiger and lion bone industry. Lion farming, in small enclosures, adds no value to lion conservation. It is an unpleasant, corrupt industry with huge animal welfare issues. South Africa has done itself severe reputational damage by its engagement in the lion bone industry and its legalised sales quota of lion bones to Asia. Namibia should steer well clear of any such trade, with severe penalties for transgressors.

A trade in ivory, by contrast, would have conservation benefits. Ivory derived from natural mortalities and from the legal management of elephant populations would help offset the cost of living with elephants, on both communal and freehold land. However, exporting raw ivory would be to lose much of the potential value. A local ivory carving and manufacturing industry would add considerable value to this natural product. In addition, the production of elephant leather and use of elephant hair would increase the value of elephants on farmlands and open up areas to elephants where they are currently not wanted. This would reduce conflicts and lead to an increased population over a larger range – all desired conservation outcomes.

Question: You mention the benefits of farming rhinos in extensive ecosystems, which provides an economic incentive for conserving large landscapes; however, one could produce more horn per year if the rhinos are kept at high densities under intensive management conditions (i.e. in captivity). What incentives do you think are needed to ensure that rhinos are kept as part of large, natural ecosystems, rather than as captive farm animals?

Answer: I would make it a condition of black rhino ownership that they could only be acquired, held and sold on if they were kept in large open systems. This would apply to black rhino ownership into the future and would be a permit requirement. Second, large open systems offer both conservation and economic benefits to the owners and custodians. In addition to harvesting of rhino horn, such systems would support a full suite of wildlife species around which various tourism products could be developed. They also allow sustainable wildlife harvesting for meat and trophies, and live sale of surplus high value species. This provides a diversified set of economic activities.

Concluding remarks: I believe that the time is right for Namibia, preferably in partnership with neighbouring countries, to take some bold steps regarding rhino horn and rhino management, for the purpose of long-term rhino conservation. The demand for rhino horn will grow. We can grow the supply. I believe we can do it in a way that protects, conserves and grows our rhino populations while harnessing the economic opportunities thus created and realising a suite of other conservation and socio-economic benefits. Namibia would then be “optimising its global comparative competitive advantages” as we are challenged to do by Vision 2030. Not to do so would have us miss huge economic opportunities while we witnessed the inevitable decline of rhinos, accompanied by a “rhino war” of attrition where everyone would be the loser.

Interview by Gail Potgieter

Hunting and tourism in Namibia

Dr Chris Brown, Namibian Chamber of Environment writes:

I am not a hunter. Nor have I ever been. I am a vegetarian (since the age of about 11), I am part of the environmental NGO sector and I have interests in the tourism industry in Namibia.

So, it might surprise you that I am a strong supporter of the hunting industry in Namibia, and indeed, throughout Africa. Having said that, I should qualify my support. I am a strong supporter of legal, ethical hunting of indigenous wildlife within sustainably managed populations, in large open landscapes. The reason is simple. Well-managed hunting is extremely good for conservation. In many areas, it is essential for conservation.

There is much confusion and misconception, particularly in the urban industrialised world and thus by most western tourists that visit Namibia, about the role of hunting in conservation. Urban industrialised societies, and I include many biologists and recognised conservation organisations in this grouping, see hunting as undermining conservation, or the anathema of conservation. And they see protecting wildlife and removing all incentives for its consumptive use as promoting and achieving good conservation. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Much of the hunting and sustainable utilization debate within conservation has been taken over by the animal rights movement. I have sympathy for people who stand up for animal rights – I think we all should. None of us want to see animals suffering or being treated badly by members of our species. But the problem arises when animal rights agendas are passed off as conservation agendas. Animal rights agendas are not conservation agendas. Conservation works at the population, species and ecosystem levels. Animal rights works at the individual level. And what might be good for an individual or a collection of individuals might not be good for the long-term survival of populations, species and biodiversity. Take a simple domestic example. When the farm carthorse was replaced by the tractor, carthorses no longer had to work long hours in the fields. But they also no longer had a value to farmers. Once common, they are now extremely rare. Indeed, carthorse associations have been established to keep these breeds from dying out. The truth is, if animals do not have a value, or if that value is not competitive with other options, then those animals will not have a place, except in a few small isolated islands of protection. And island protection in a sea of other land uses is a disaster for long-term conservation.

Animal rights are important. But for wildlife they must be placed within a sound conservation and animal welfare setting, where conservation decisions on behalf of populations, species and ecosystems take priority over the rights of individual animals, but with due consideration of their welfare. Ethical and humane practices are an integral part of good conservation management and science.

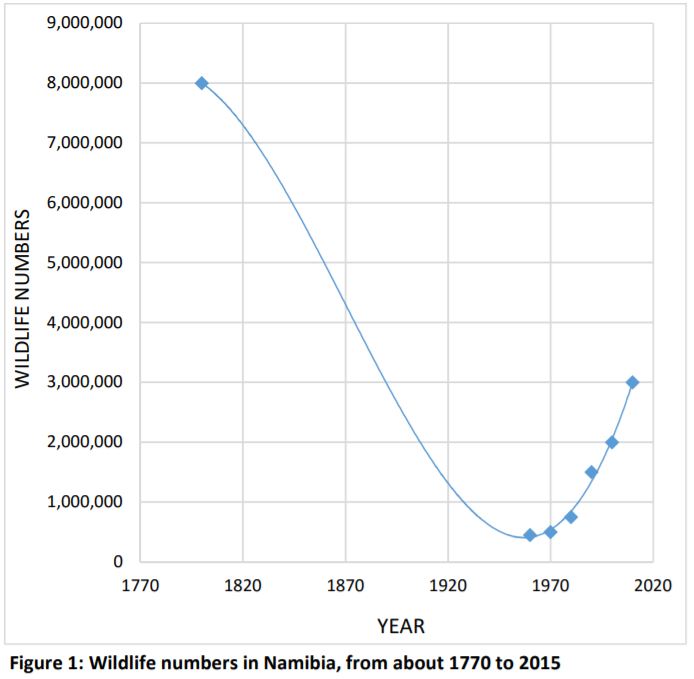

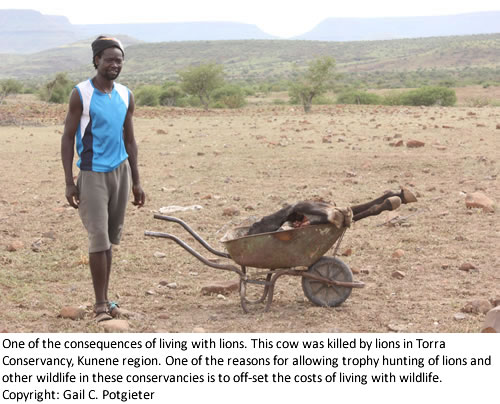

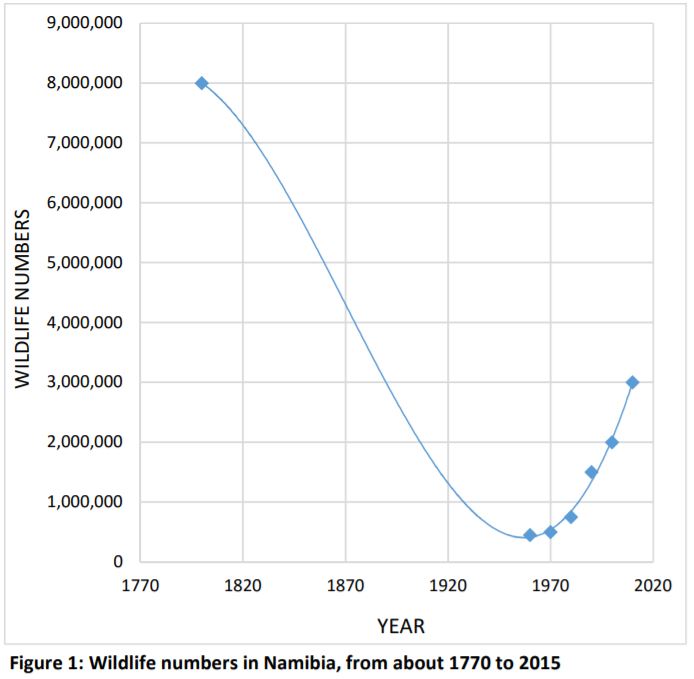

The wildlife situation in Namibia provides a very good example of this. When the first western explorers, hunters and traders entered what is now Namibia in the late 1700s, crossing the Orange / Gariep River from the Cape, the national wildlife population was probably in the order of 8-10 million animals. Over the following centuries wildlife was decimated and numbers collapsed, first by uncontrolled and wasteful hunting by traders and explorers, then by local people who had acquired guns and horses from the traders, then by early farmers, veterinary policies and fencing, and finally by modern-day farmers on both freehold and communal land who saw wildlife as having little value and competing with their domestic stock for scarce grazing. Traditional wildlife management under customary laws administered by chiefs had broken down under successive colonial regimes. By the 1960s wildlife numbers were at an all-time low in Namibia, with perhaps fewer than half a million animals surviving (Figure 1).

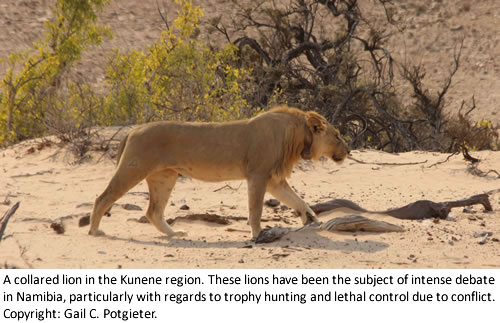

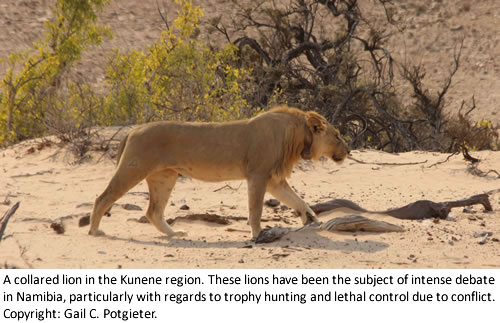

At that time wildlife was “owned” by the state. Land owners and custodians were expected to support the wildlife on their land, but they had no rights to use the wildlife and to derive any benefits from wildlife. In response to declining numbers and growing dissatisfaction from farmers, a new approach to wildlife management was introduced. In the 1960s and 1990s, conditional rights over the consumptive and non-consumptive use of wildlife were devolved to freehold and communal farmers respectively, the latter under Namibia’s well known conservancy programme. The laws give the same rights to farmers in both land tenure systems. This policy change led to a total change in attitude towards wildlife by land owners and custodians. Wildlife suddenly had value. It could be used to support a multi-faceted business model, including trophy hunting, meat production, live sale of surplus animals and tourism. It could be part of a conventional livestock farming operation, or be a dedicated business on its own. As the sector developed, so farmers discovered that they could do better from their wildlife than from domestic stock. Both small- and large-stock numbers declined on freehold farmland while wildlife numbers increased. Today there is more wildlife in Namibia than at any time in the past 150 years, with latest estimates putting the national wildlife herd at just over 3 million animals. And the reason is simple – wildlife is an economically more attractive, competitive form of land use than conventional farming in our arid, semi-arid and dry sub-humid landscapes. Markets are driving more and more farmers towards the management of wildlife. This is good for conservation, not just from the perspective of wildlife, but also from the broader perspective of collateral habitat protection and biodiversity conservation. The greater the benefits that land owners and custodians derive from wildlife, the more secure it is as a land-use form and the more land there is under conservation management. Therefore, all the component uses of wildlife, including and especially trophy hunting, must be available to wildlife businesses. These uses include the full range of tourism options, live sale of surplus wildlife, and the various forms of consumptive use – trophy and venison hunting and wildlife harvesting for meat sale, value addition and own use. It is this combination of uses that makes wildlife outcompete conventional farming. And it is the “service” component of tourism and hunting that elevate wildlife values above that of primary production and the simple financial value of protein. As the impacts of climate change become ever more severe, so will primary production decline in value, but not so for the “service” values derived from arid-adapted wildlife. And why especially trophy hunting? Because there are large areas of Namibia comprising remote, flat terrain with monotonous vegetation that are unsuited to tourism, but very important for conservation.

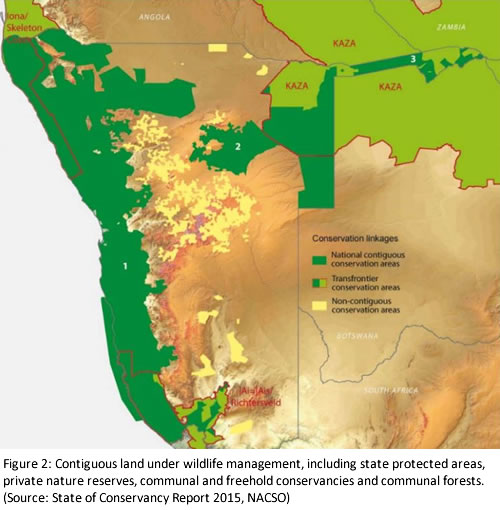

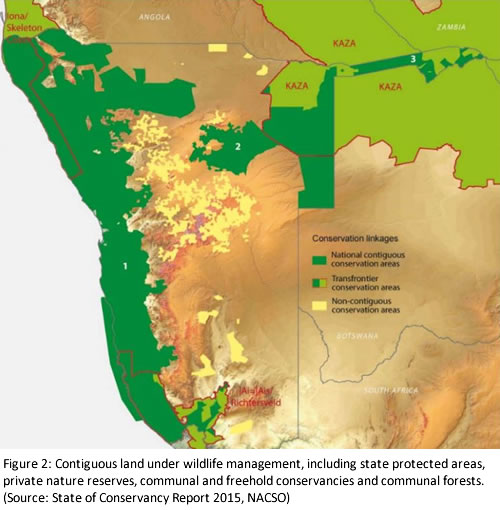

If Namibia had adopted an animal-rights based, protectionist, anti-sustainable use approach to wildlife management, we would probably today have fewer than 250,000 head of wildlife (just 8% of our present wildlife herd) in a few isolated large parks and a few small private nature reserves. We would have lost the connectivity between land under wildlife, and we would have lost the collateral conservation benefits to broader biodiversity, natural habitats and ecosystem services. Today, Namibia has well over 50% of its land under some form of formally recognised wildlife management (but probably over 70% if informal wildlife management is considered), including one of the largest contiguous areas of land under conservation in the world – its entire coast, linking to Etosha National Park and to conservation areas in both South Africa (Richtersveld) and Angola (Iona National Park) – over 25 million ha (Figure 2).

There are some people in the tourism sector in Namibia and in our neighbouring countries who oppose trophy hunting because it is perceived to conflict with tourism and is thus not good for conservation. Some suggest that the land and its wildlife should be used for eco-tourism and not hunting. In most areas, eco-tourism cannot substitute for hunting. The loss of hunting revenue cannot be made up by eco-tourism revenue. Indeed, we need to optimise all streams of wildlife-derived revenue to make land under wildlife as competitive as possible.

Some tourism operators and tour guides attack the hunting sector to their guests. These tourism operators and guides are undermining an important part of conservation, an important contributor to making land under wildlife competitive and, in the final analysis, they are undermining the viability of conservation as a land-use form. The greatest threat to wildlife conservation, in Namibia and globally, is land transformation. Once land is transformed, often for agricultural purposes, it has lost its natural habitats, it has lost most of its biodiversity and it can no longer support wildlife. Hunters and tourism operators should and must be on the same side – to make land under wildlife more productive than under other forms of land use. They are natural allies. They need to work together to ensure that land under wildlife derives the greatest possible returns, through a multitude of income earning activities. And where it is necessary for both hunting and tourism to take place on the same piece of land, they need to plan, collaborate and communicate so that all aspects of wildlife management and utilization – both consumptive and non-consumptive – can take place without one impacting negatively on the other. Conflicts between hunting and tourism are simply failures of management and communication, nothing more profound than that. But the onus should be on the hunting outfitters to ensure that there are ongoing, good communications. The onus is also on hunting outfitters, professional hunters, and the hunting sector to always maintain the highest ethical and professional standards, and to be mindful of the sensitivities of many people to the issue of hunting.

It is also the vital task and duty of tourism operators and guides to educate visitors from the urban industrialised countries about conservation in this part of the world. Visitors need to understand what drives conservation, the role of incentives, markets and what is meant by sustainable wildlife management. The tourism sector should not skirt around an uncomfortable discussion on hunting, but face it head-on and explain its importance to conservation. This is what good education is all about. Tourists come to Namibia to be enlightened, to be exposed to new ideas and to better understand the issues in this part of the world. They come here to take back new and interesting stories. What better story than Namibia’s conservation successes. But visitors need to understand it properly – its incentives, its market alignment, its strong links to the local and national economy, and its role in addressing rural poverty. It is the task of the tourism industry to help visitors understand why Namibia has one of the most successful conservation track records of any country in the world.

If we look for a moment at the conservation trajectory of a country such as the United Kingdom (an urban industrialised example) through its agrarian and industrial development, the indigenous wildlife at that time had no value. Thus, it lost the elk, wild boar, bear, wolf, lynx, beaver and sea eagle – essentially its most charismatic and important species. While small-scale attempts to reintroduce a few of the less threatening species are underway, it is unlikely that it will ever reintroduce the bear and wolf into the wild as free-ranging populations. And yet that country and others like it, with poor historic conservation track records, are keen to influence how Namibia should manage its wildlife. Its own farmers are not prepared to live with wolves, but many of their politicians and conservation agencies, both public and non-governmental, expect Namibian farmers to live with elephant, hippo, buffalo, lion, leopard, hyaena, crocodile and many other wildlife species that are far more problematic from a human-wildlife conflict perspective than a wolf. And they try to remove the very tools available to conservation to keep these animals on the land – the tools of economics, markets and sustainable use, to create value for these animals within a well-regulated, sustainably management wildlife landscape.

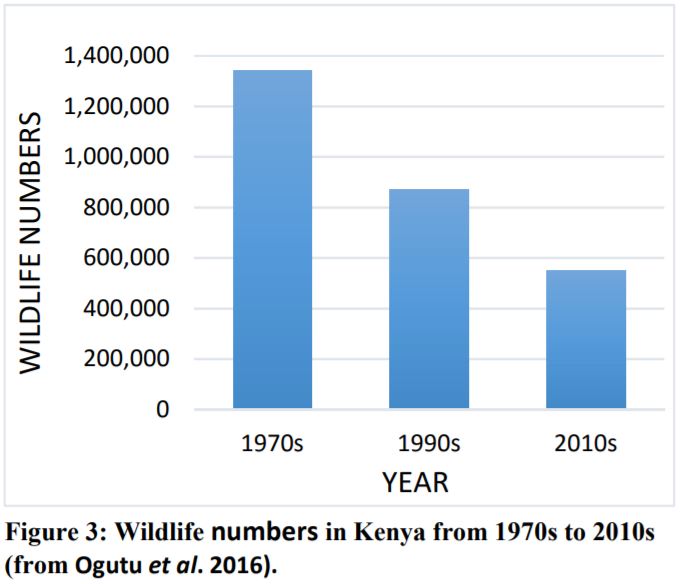

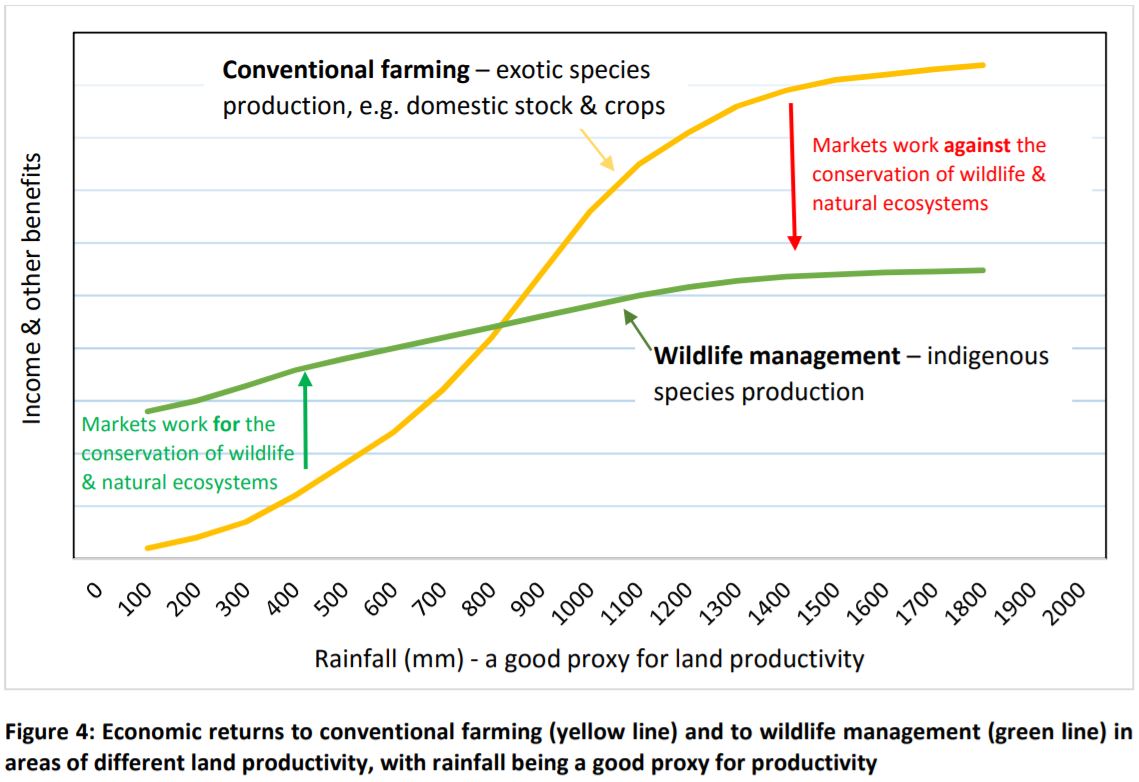

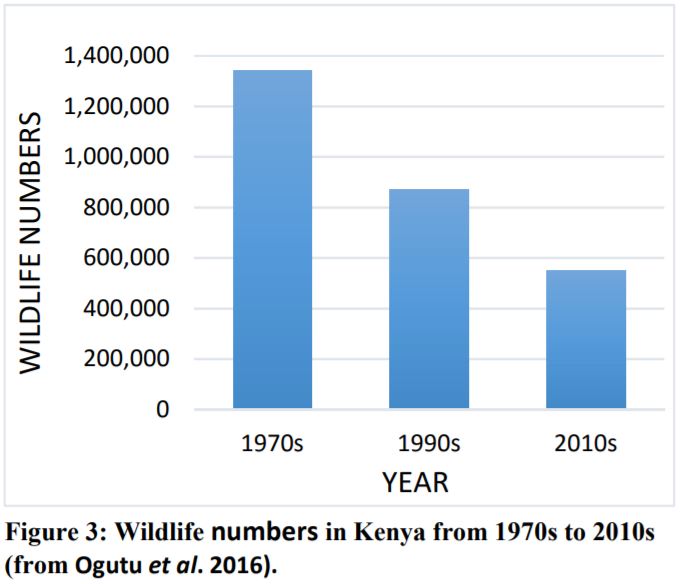

I believe that the problem is essentially one of ignorance. People think that they are doing what is best for conservation, but they simply do not understand the economic drivers for wildlife and biodiversity conservation in biodiversity-rich and rainfall-poor developing countries. And many African countries are sadly falling into the same trap. Kenya, for example, with its Eurocentric protectionist conservation approaches, has less wildlife today than at any time in its history (Figure 3). We need to share the message. And the message is, I believe, most powerfully explained using the simple graphic in Figure 4.

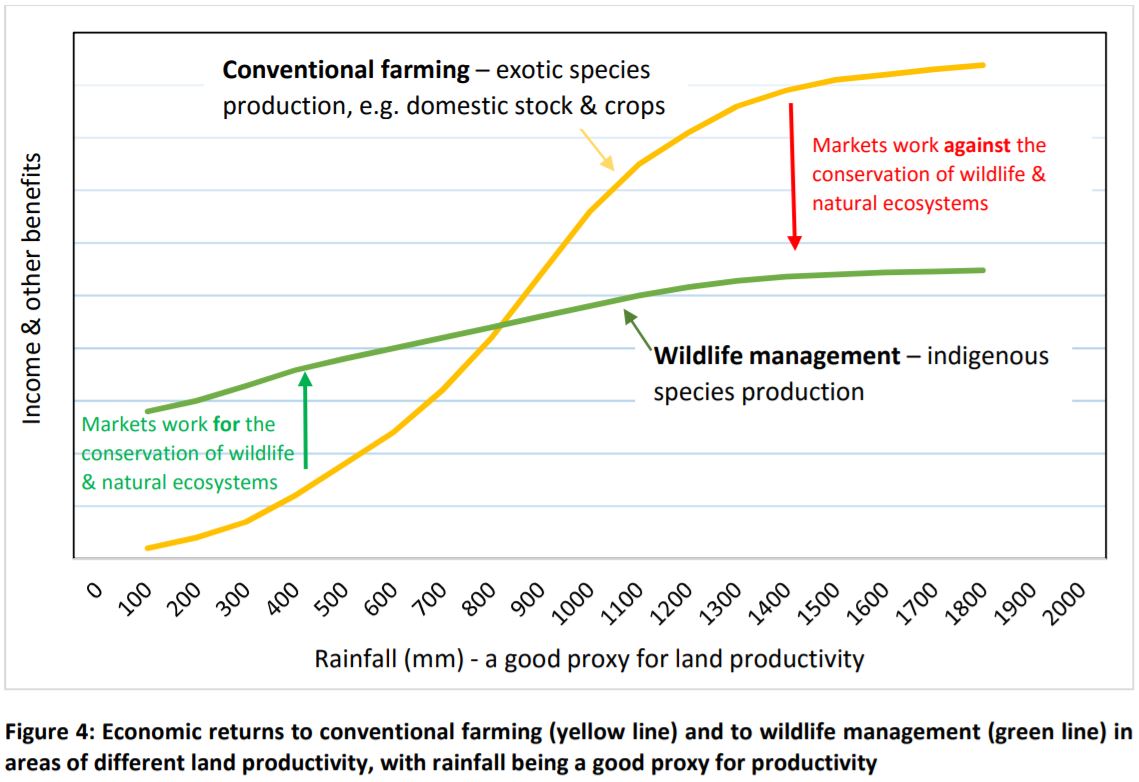

The yellow line represents the return to land use under conventional farming, e.g. domestic stock and crops, across a rainfall gradient – rainfall being a proxy for land productivity. The green line shows the returns to land under wildlife. On the left side of the graph, in areas of rainfall below about 800 mm per year, returns from “indigenous production systems” – i.e. wildlife, are greater than the returns from “exotic production systems” – i.e. farming. However, this only applies if the rights to use wildlife are devolved to land owners and custodians. Markets then create a win-win situation for optimal returns from land and for wildlife conservation in these more arid areas. If utilisation rights are not devolved, then wildlife has little value to the land owner and custodian, and people will use the land for other activities. On the right side of the graph, above about 800 mm, the lines cross over and here conventional farming outperforms wildlife management. If land owners and custodians are given rights over the wildlife and other indigenous species on their land, they will get rid of these species and transform the land for farming in response to market forces. Most of the western, industrialised world falls into the right side of the graph. Conservation agencies and organisations from countries on the right side of the graph, and areas where rights over wildlife are not devolved to land owners, are so conditioned to resist and fight against market forces having negative conservation impacts in their countries, that they automatically carry the fight across to those countries falling into the left side of the graph and which have devolved wildlife rights, not realising that the lines have switched over and that markets here are working for conservation. This is the important message that we must get across to policy makers, conservation organisations and the broader public in the urbanised and industrialised countries. And in some other parts of Africa. People need to understand the conservation drivers, incentives and markets, as well as the role of sustainable use within good conservation policy and practice. Well-intentioned but poorly informed efforts to influence conservation in this region seriously undermine good conservation policies and practices.

A second insight from Figure 4 is that the greater the value earned from wildlife, not only is the gap widened on the left side of the graph over conventional farming, but the crossover point is pushed further to the right. This means that higher rainfall areas become competitive under wildlife management, opening more of Africa to this form of land use.

Namibia’s record of environmental accomplishment speaks for itself. Through the implementation of appropriate policies, it has created incentives for wildlife conservation, unmatched anywhere in the world. But wildlife must have value otherwise land owners and custodians will move to other forms of land use. And it must have the greatest possible value to be as secure a land use as possible, over the largest possible landscape. And that is why I strongly support well-managed and ethical hunting. It is good, and in some cases essential, for the conservation of wildlife, of habitats and of biological diversity. And that is why hunting and tourism must work together, in mutually supportive ways, to optimise returns from wildlife for the land. Well managed and ethical hunting should in fact be called “conservation hunting”. And conservation hunting is essentially an integral part of tourism.

April 2017

Bibliography

Barnes JI 1998. Wildlife conservation and utilisation as complements to agriculture in southern African development. Research Discussion Paper No 27, Directorate of Environmental Affairs, Ministry of Environment and Tourism, Namibia. http://www.the-eis.com/data/RDPs/RDP27.pdf

Barnes JI 2001. Economic returns and allocation of resources in the wildlife sector of Botswana. South African Journal of Wildlife Research 31(3/4): 141-153.

Barnes J, et al. 2004. Preliminary valuation of the wildlife stocks in Namibia: wildlife asset accounts. Internal report, MET. Windhoek. 9 pp. http://www.the-eis.com/data/literature/Preliminary%20valuation%20of%20t…

Barnes JI & de Jager JLV 1995. Economic and financial incentives for wildlife use on private land in Namibia and the implications for policy. Research Discussion Paper No 8, Directorate of Environmental Affairs, Ministry of Environment and Tourism. http://www.the-eis.com/data/RDPs/RDP08.pdf

Di Minin E, Leader-Williams N & Bradshaw CJA 2016. Banning trophy hunting will exacerbate biodiversity loss. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 31(2): 99-102.

IUCN 2016. Informing decisions on trophy hunting. IUCN Briefing Paper April 2016, 19 pp.

Lindsey P 2011. Analysis of game meat production and wildlife-based land uses on freehold land in Namibia: Links with food security. A Traffic East/Southern Africa Report. 81 pp.

Lindsey PA, Havemann CP, Lines RM, Price AE, Retief TA, Rhebergen T, van der Waal C. & Romanach S 2013. Benefits of wildlife-based land uses on private lands in Namibia and limitations affecting their development. Fauna & Flora International, Oryx 47(1): 41–53.

Munthali SM 2007. Transfrontier conservation areas: Integrating biodiversity and poverty alleviation in Southern Africa. Natural Resources Forum 31: 51-60.

NACSO 2015. The state of community conservation in Namibia. NACSO, Windhoek. 80 pp. http://www.nacso.org.na/sites/default/files/The%20State%20of%20Communit…

Naidoo R, Weaver LC, Diggle RW, Matongo G, Stuart-Hill G & Thouless C 2015. Complementary benefits of tourism and hunting to communal conservancies in Namibia. Conservation Biology. Published online October 13, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12643

Norton-Griffiths M 2010. The growing involvement of foreign NGOs in setting policy agendas and political decision-making in Africa. First published by Blackwell Publishing, Oxford Institute of Economic Affairs 2010. 5pp.

Ogutu JO, Piepho H-P, Said MY, Ojwang GO, Njino LW, Kifugo SC, et al. 2016. Extreme Wildlife Declines and Concurrent Increase in Livestock Numbers in Kenya: What Are the Causes? PLoS ONE 11(9): e0163249. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0163249.

Stemmet E 2017. The ban on hunting in Botswana’s concession areas. African Outfitter Jan/Feb 2017: 38-42.

Wilson GR, Hayward MW & Wilson C (in press). Market-based incentives and private ownership of wildlife to remedy shortfalls in government funding for conservation. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12313.

Bush Talks: Conversations to Foster Sustainable Biomass Utilization

Statement on Potential Namibian Biomass Export to Hamburg

Are you eating plastics for dinner?

Conservation Partnerships to combat wildlife crime in Namibia

Feral horses in the southern Namib parks

Response to Concerns About Wildlife Numbers in Namibian Communal Conservancies